Questions On Cash Flow Business Loans:

1) Can I borrow a cash flow loan to buy a business?

2) What is a cash flow loan?

3) Who are the cash flow lenders?

4) How much cash flow do I need to get a cash flow loan?

Does anyone really know what a cash flow loan is? When I work with students I teach how to procure loans on an asset based basis. You need assets for an asset based loan. But a cash flow loan is theoretically different. Instead of assets to back the loan you need cash flow. Sound silly? It almost is silly because cash flow loans are almost a thing of the past. Ever since the very first leveraged buyout lenders have become more street smart and have become more conservative about making cash flow loans. Especially banks, who have been burned countless times by poor lending practices and have had to modify their lending policies any number of time over the years.

First, let me answer the question as to what a cash flow loan is. A cash flow loan could be a few different things. It could be a mezzanine loan for example, which, as you may remember is a “junior” loan as opposed to a senior bank type loan. Mezzanine is more expensive but needs less or no collateral. This is typical of bigger transactions upwards of $5 Million in transaction size.

It could be a bank term loan which might be a senior loan but not based so much on collateral as is it’s primary working capital line.

It could even be an equipment lease for example where the equipment is hardly worth enough to cover the loan but the cash flow is strong enough to give the lender some comfort.

In summary any loan which depends on a steady stream of net cash flow from the borrower is a cash flow loan. It still may be secured by assets but usually not enough to justify the loan.

Note that we may not be talking about net income here but rather cash flow, which is a number that adds back non-cash items like depreciation and possibly timing differences. And when we talk about cash flow we mean cash flow after paying all the other expenses and debt service.

The Story of Specialty Lender

So let me take you back a few years to illustrate what a cash flow loan was in its prime. There once was a company named Greyhound Financial which ultimately changed the name to Finova Capital Corp. During the adolescent years of LBO’s and through the 90’s this company did something few other lenders did. It facilitated buyouts with a cash flow product nobody could match. Essentially it could provide in a one-stop-shop, a big cash flow loan to buy pretty much any small company a small buyer could want.

This loan might have run five to seven years in a term loan plus a working capital line and the buyer only had to put up 10-15% equity if that. The lender took a “kicker” which might have been 15% of the equity in the deal. But it didn’t always end up as common stock, it could also put annual cash bonuses in the pocket of the lenders and their lending staff of substantial amounts. Later the practice of awarding incentive bonuses on loans would be criticized as a conflict of interest since lenders were charged with protecting the quality of their loans, as well as originating them.

The collateral didn’t matter, in fact they often didn’t even take the collateral available. As lender sometimes do, they took “side collateral”. Side collateral is another word for “not enough collateral” which means if the lenders sold off the collateral to pay for a deal gone bad they wouldn’t get much, certainly not enough to get their loan paid.

Everyone loved the Finova product. People who had no business buying companies could do leveraged buyouts even if the company didn’t have much in the way of assets. All that really was required was that the target company could demonstrate cash flow that could meet its annual debt obligations by a small margin. So whatever happened to Finova? Well, after making too many risky loans it got itself into trouble, as many lenders do, and it folded some years ago.

The point is that Finova really isn’t unique by today’s standards. While it was a lending pioneer back in the day, these days lenders turn up constantly with new products, many of which are cash flow based loan products. Indeed some of my best deals have been done with brand new lenders who just burst onto the scene with an aggressive loan product and plenty of money to lend.

Main Street Banks

Any main street bank, small or big, is a good example of a cash flow lender. But it is far more common for them to be collateral lenders and take cash flow into account in the underwriting. A bank will rarely lend a lot of money with absolutely no collateral. Depending on the lending climate they can be reasonably aggressive or, on the other hand, nearly shut out from making loans. The problem is they are not risk takers and are not always useful for a buyout. For example the typical loan package is either for an existing customer or an new business that is in very good shape and agrees to use the bank for their operating accounts. Their first priority is actually deposits and not loans so the two are usually wrapped up together in any offer they make.

Loans from a bank are generally quite cheap because they don’t take that extra risk… and because their return is augmented by the customer deposits they take in which pay the customer nothing or next to nothing in interest. They can put these deposits to work and make the “spread” whereby they lend the cheap customer deposits out at higher rates. Even at this writing the bank stocks have risen at the prospect of the Fed increasing rates, as any such increase will improve the spread and hence a bank’s bottom line.

Can A Cash Flow Loan Be Used For An Acquisition?

Yes and No. In theory any loan can be used for an acquisition. As I pointed out above there have been lenders that thrive on cash flow loans for acquisitions. There still are many out there – but the world is somewhat different after the recession in 2008 and lenders are never quite as aggressive as they were the decade before. But new lenders that are hungry take their place. It is a matter of finding them.

Cash flow lending generally has a higher standard of credit criteria than collateral based loans. The deal must be better, it cannot be a turnaround or questionable deal. It cannot be losing money. Barring mezzanine financing, the cash flow loan will be a minor component of an acquisition deal if at all. Asset based lenders used what is called an “airball” to describe a portion of a financing package which is unsecured or not covered adequately by the asset base. They do not embrace unsecured loans, but sometimes make an exception for a small part of the loan package.

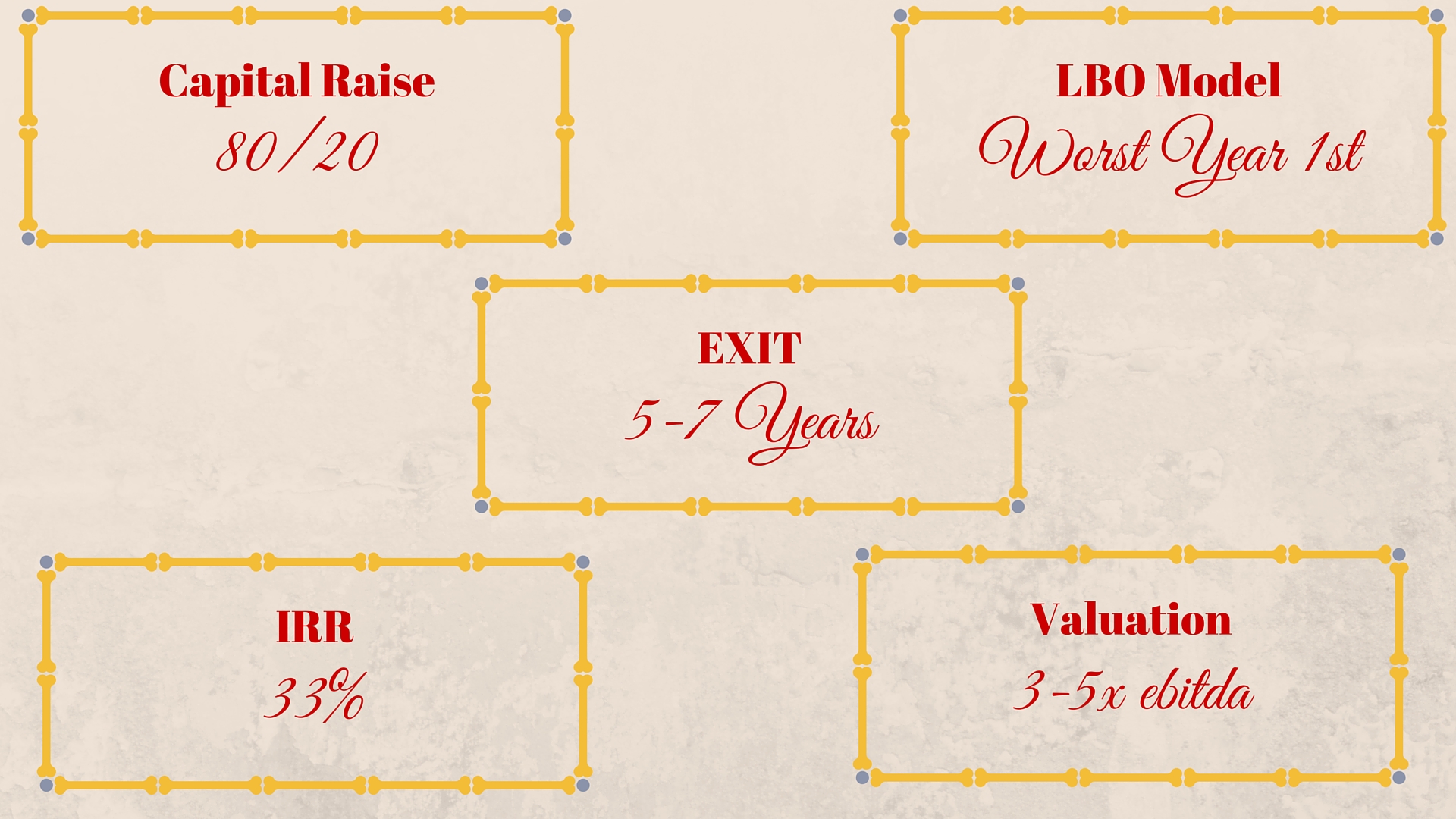

The days of the majority of the financing package being unsecured are pretty much gone, except for deals in the larger market which could be upwards of $3mm EBITDA where the cash flow is substantial and attracting large one-stop senior lenders, mezzanine funds and even private equity. These deals generally require a loan size of $3-$5mm and up. Generally new guys in the deal business shouldn’t chase those big deals (the main reason being the front costs, not from lack of equity in the world) although I have done so on numerous occasions.

Stuctures of A Cash Flow Loan

Since a cash flow loan can come from many sources (banks, SBA, private lenders, mezzanine lenders, investors) they can take many different forms. Traditional banks will provide a five year term loan complete with covenants and a low rate (base rate plus 1-3%) in exchange for a good credit, side collateral (whatever is available in the business) and personal guarantees. The new breed of lender that can be very aggressive will lend small amounts at high rates just like a factor. The rates can come in the form of fees and short term maturities.

As a general rule cash flow loans are made using some key credit criteria which take into account the total cash flow of the company and match it against the total debt service. If there is no acquisition involved the analysis is simple. If an acquisition is involved the analysis must take into account the new debt being created as well as any other projected changes to the bottom line. This makes things tricky for the lender as he must rely on some guesswork and projections.

In the simplest form the typical cash flow loan must meet an initial “coverage ratio” which is generally in the 1.20/1.00 range. Or the annual cash flow must exceed the annual debt service by about 20%. It could be less or more. I have always tried to put together acquisitions that do at least 1.50/1.00 coverage EBITDA/Debt service without taking into account any effect from taxes. This should satisfy most lenders, even if the ratio were quite a bit lower.

Ultimately taxes will have an effect: a) taxes paid increase debt service b) interest and depreciation deductions reduce debt service(since they reduce taxes). To make life easier I ignore the two on the assumption they will offset each other presume to use raw EBITDA versus raw debt service. In the LBO modelling the precise effect of taxes can be used.

The maturities of a cash flow loan are usually short, five years or less. The more stable the collateral the longer the term, which is why real estate loans go out more than ten years. If you have no collateral, the loans are easily callable and remain short term. The most common cash flow loan is your credit card or an open seasonal line of credit for a business. Both can be instantly revoked. The credit cards can theoretically remain outstanding for a long period of time racking up huge interest costs, but the risks are mitigated by the small amounts typically granted to the individual borrowers. A small business cash flow line is fast becoming the same product as a big credit credit card account.